How Zanzibar Revolution dragged Jomo Kenyatta, Oginga Odinga and British Spies into great conflict

The Zanzibar Revolution which occurred in January 1964 became the first catalyst in the enmity between former political friends Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, then Prime Minister of Kenya and his Home Affairs Minister Oginga Odinga.

Even though British and American spy agencies stated that they didn’t have anything linking Odinga with the revolution, they guessed that as Moscow’s key ally in East Africa there was a possibility that he was involved.

During those days it was fashionable for the West to blame Moscow for any insurgency.

In the aftermath of the revolution the MI5 Liaison Officer in Nairobi advised the Governor General of Kenya, Sir Malcolm MacDonald and Tom Mboya, to warn the Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta against Oginga Odinga.

The British spy in Kenya wanted Kenyatta to grant the Special Branch permission to start monitoring Oginga Odinga because he was “likely to overthrow him in future!”

Tom Mboya went to Kenyatta’s home in Gatundu and raised the matter with the Prime Minister.

However, Mzee Kenyatta dismissed him straightaway.

Similar attempts by the Governor to have Odinga monitored were dismissed by Kenyatta who believed that there was no way his friend could instigate a coup against him.

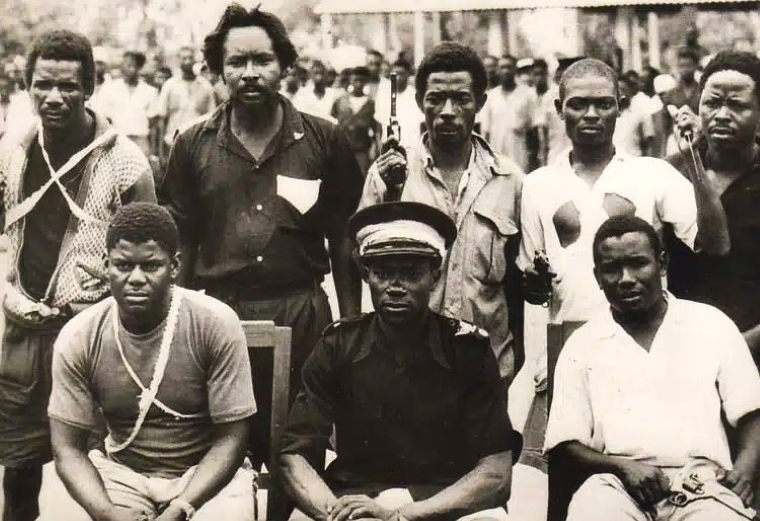

But things took a drastic turn and Kenyatta’s perception against Odinga changed all of a sudden when rumours emerged that John Okello a proxy who by that time was believed to have led the Zanzibar revolution had entered Kenya with the permission of the Minister for Home Affairs Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

This provided fodder for American and British spy agencies to drive a wedge between Kenyatta and Odinga.

They warned Kenyatta that the presence in Kenya of someone who had instigated a revolution in Zanzibar, brought the risk of a coup directly on Kenyatta’s doorstep and the sooner he took steps against Odinga who had permitted Okello to enter Kenya, the better.

As soon as rumours about the presence of Okello in Kenya began to circulate, Sir Richard Catling, the Commissioner of Police at that time, flew almost immediately to Mombasa on 21st February 1964 to inform the Prime Minister Kenyatta about it.

That same evening Kenyatta summoned Odinga to a meeting during which a bitter exchange ensued between them.

According to declassified files of the meeting Kenyatta asked Odinga why he had allowed Okello to enter Kenya without following immigration rules.

Odinga replied that as Minister in charge of immigration he had the powers.

“But l am the Prime Minister,” Kenyatta interrupted him.

A very heated row developed with Odinga telling Kenyatta that he had no intention of overthrowing his government or competing with him, pointing out that if he wanted to do so, then he could have done it when Kenyatta was in prison.

James Gichuru the Minister for Finance who was present during the exchange, would later confide in the British High Commissioner to Kenya, that the exchange was so bad that Kenyatta’s blood pressure went so high; “he became quite unwell forcing him to cancel most of his coastal engagements.”

Kenyatta then issued instructions that every effort be made to find Okello and kick him out of the country.

But one thing that government officials forgot in their efforts to trace Okello was that immigration laws of Kenya did not apply to citizens of East African territories.

In other words, John Okello essentially did not need permission to enter Kenya.

This presented a big legal obstacle in carrying out the prime minister Jomo Kenyatta’s orders which were being executed by the minister of state in the Prime Minister’s Office Joseph Murumbi .

To overcome these obstacles legal draughtsmen were put in place to work urgently to produce a bill enabling immigration controls to be imposed on citizens of other East Africans countries entering Kenya.

The objective was to push it through quickly and very soon.

Meanwhile the search for Okello who had already escaped to Uganda was being pursued vigorously by the Principal Immigration Officer and the Special Branch.

At one point they ended up tracking the wrong John Okello, a Kenyan Government Officer who was in Nairobi visiting his relatives.

Although the British associated Odinga with the Zanzibar Revolution, they admitted to having no evidence linking him but claimed they had enough proof linking him to Okello’s escape.

On 22nd Feb 1964, a day after his bitter exchange with Kenyatta and in a bid to disassociate himself from the events in Zanzibar, Odinga released a statement blaming his woes on the British.

“….l strongly disagrees with this claim by which the British are trying to avoid responsibility for what took place in Zanzibar. It was the British who encouraged unjust policies in Zanzibar which were intended to make the minority rule over the majority.

“The constituencies in Zanzibar were demarcated in such a way so as to frustrate the most popular party. It was these undemocratic practices that were at the root of the violent explosion in Zanzibar. The British imperialists, knowing that their underhand work has been exposed, tried to find scapegoats in the form of communists and people like me.

“We in Kenya do not approve violence as a means of changing Governments. It was in this spirit that I contacted Abeid Amani Karume, the President of Zanzibar expressing our disapproval of the intended hanging of ex-Ministers.

“Malicious insinuations have been made that I was in contact with John Okello, the alleged leader of the revolution .This is absolutely nonsense. I have never known this man John Okello and have never talked with him at any time.

“If anybody in Kenya should be in doubt about myself or about my political intentions, he would be doing me a great injustice. I have always stated my policies openly and frankly. The essence of my policy is that I am dedicated to work with my fellow Africans and liberal minded people for the complete abolition of Colonialism.”