Why is the global aid system fragmenting? And what is the World Bank advising as the only solution?

Aid architecture refers to the framework of rules and institutions governing the distribution of aid to developing countries, as well as the flow of aid to developing countries through such a framework.

Now, aid architecture has become increasingly complex over the past decades, with more countries becoming donors, more development agencies created, and more channels of aid flows established.

Proliferation of Donor Channels

The global aid architecture has undergone significant transformation over the past 25 years, developing predominantly without a clear blueprint.

Current aid practices have remained largely unchanged since they were established following World War II.

The financial flows to developing countries are increasingly organic, which undermines the effectiveness of aid. Emerging economies are now joining traditional donors as bilateral providers of Official Development Assistance (ODA).

Between 2011 and 2023, 19 percent of the bilateral loans to developing countries originated from emerging economies such as China, Russia, India, and Saudi Arabia.

During this period, the World Bank has remained the primary source of financing, contributing $504 billion in loans and grants.

Other MDBs have provided USD 457 billion in ODA, with IDA representing 71 percent of this total.

Increased funding for global development is undoubtedly beneficial.

However, the global aid system has become increasingly complex, burdening recipient countries with limited capacity to handle it.

This complexity has also created challenges for effective aid delivery, influenced by globalization and changing donor priorities.

Four Mega Trends

Between 2004 and 2023, the number of donors went up from 63 to 118 and the number of donor agencies increased dramatically, rising from 227 to 622.

The Hidden Cost of Proliferation

Recipient countries face challenges from multiple donors, each requiring a specific documentation such as project audits, procurement reports, financial statements, and progress updates.

Unfortunately, these requirements often differ significantly from one donor or agency to another, creating a lack of standardization.

This situation limits the potential for policy influence and can lead to conflicts, making aid management more complicated and increasing transaction costs.

As a result, valuable resources and time are diverted away from essential development initiatives, ultimately hindering progress and stability.

The increase in donor proliferation has led to the fragmentation of aid flows, especially Official Development Assistance (ODA). Currently, the average ODA grant per activity is less than 60 percent of what it was two decades ago.

Between 2000 and 2023, the size of ODA grants went from an average of USD 1.5 million to USD 0.9 million.

The size of grants is especially concerning since low-income countries have a weaker capacity, and the higher transaction costs place a disproportionate burden on them.

Navigating Circumvention

A growing share of development assistance is bypassing recipient government budgets, which limits the capabilities of sovereign agencies.

Currently, three out of four projects are implemented by nongovernmental organizations, and half of these funds do not go through the budgets of the recipient countries, which undermines the effectiveness of aid.

Additionally, donor funding is increasingly earmarked for specific issues, which restricts opportunities to pool resources and enhance the overall financing available to countries.

An increasing share of official development assistance (ODA) expenditures in donor countries means less funding reaches aid recipient countries.

This trend could impact several areas:

Aid Effectiveness:

Reduced funding may lower the effectiveness of aid programs and create competition among recipient countries, undermining holistic development strategies.

Country Ownership and Alignment:

Less aid to recipient governments undermines local ownership, making it harder to lead their development policies. It may misalign aid with their priorities due to differing external agendas.

Capacity Building:

Funnelling less aid through government budgets gives fewer opportunities for strengthening local systems and administrative capacity, leaving the institutions underdeveloped and dependent on external support.

Sustainability:

Development interventions risk being unsustainable without adequate funding and government involvement in project planning and execution.

Local Economic Impact:

Aid that bypasses government budgets has a reduced impact on the local economy. Budget support fosters economic activity through public spending, which may not happen if aid is focused solely on external projects.

Needless to say, these adverse trends run counter to the direction agreed upon in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness of 2005, which had the defining message: “put the countries in the driver’s seat.”

The number of OFF transactions by nongovernmental entities has risen more quickly than the money involved, indicating a trend of fragmentation in their financial aspects.

In the past decade, OFF activities by nongovernmental entities have risen nearly 70 percent, while recipient governments have remained stable.

This change reflects the growing number of donors and donor channels.

The average financial size of transactions through nongovernment channels is consistently smaller than those conducted by recipient governments.

This kind of circumvention contributes to the fragmentation of development assistance. For instance, Ethiopia works with over 250 agencies, straining its administrative capacity.

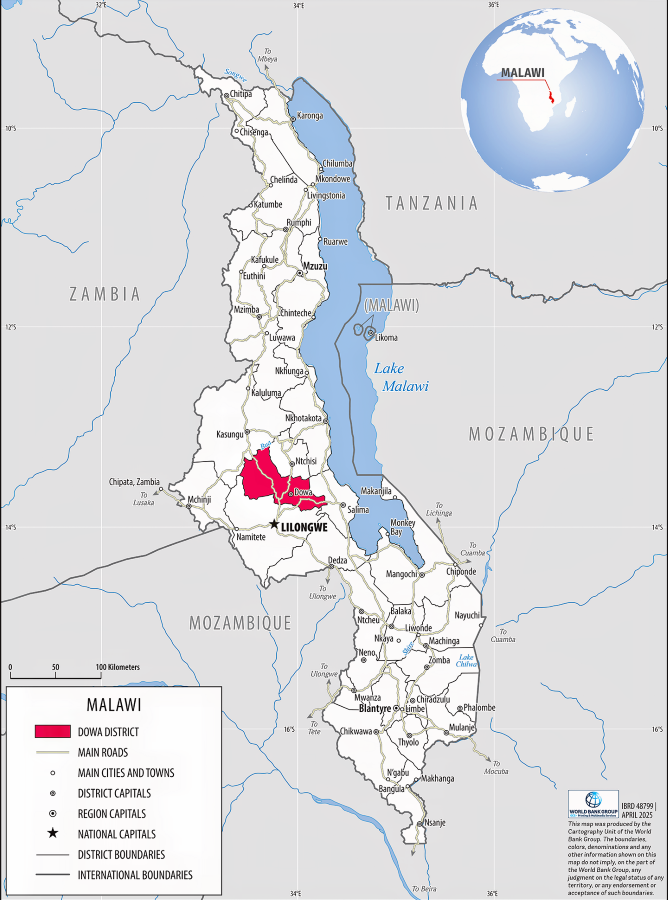

Malawi, with a population of 21.1 million (as of 2023), managed an average of 184 donor agencies from 2019 to 2023.

Meanwhile, Mozambique saw a 120 percent increase in agencies from 2004-08 to 2019-23, reaching over 222 by 2023.

These combined trends create a heavier burden on recipient countries, which often have limited institutional capacity.

They must manage numerous partners with varying priorities and bureaucratic demands, all while facing a reduction in the size of development assistance.

Rewards of Leveraging

Aid designated for specific sectors or themes, particularly through vertical platforms, has experienced significant growth. Over the past 15 years, the bilateral contributions to vertical platforms more than doubled.

In contrast, bilateral contributions to horizontal platforms have mainly remained stagnant in real terms.

Vertical approaches are effective in addressing specific issues such as HIV/AIDS or climate change and can achieve economies of scale. However, they typically operate as unleveraged facilities.

On the other hand, horizontal platforms, like IDA, function as leveraged facilities. They amplify every donor dollar by nearly four times, which enhances resource mobilization and can lead to larger long-term impacts.

IDA — Defragmenter Platform

There are various approaches to enhance aid effectiveness and simplify the complexities of aid architecture, but IDA presents the best and simplest solution.

IDA serves as a catalyst by addressing the priorities of recipient countries, enhancing government capacity, and helping manage proliferation and fragmentation. It tailors its interventions to regional and global needs, leveraging its local presence and global knowledge.

IDA acts as a global platform for governments, civil society organizations, and development agencies to coordinate and align their efforts, which helps reduce fragmentation in the global aid system.

IDA’s hybrid financial model increases its financial capacity by utilizing its triple-A credit rating.

By combining contributions from partners with low-interest capital market borrowing, IDA can mobilize up to USD 4 for every USD 1 its partners contribute.

IDA’s strengths make it a key player in the evolving global aid landscape. With rising demand for development finance, IDA’s role in providing concessional funding, grants, and promoting debt sustainability is vital for addressing current global aid challenges.

Why IDA?

IDA’s comparative advantages, global footprint, and its ability to address global challenges at the country level make it a critical player in the evolving global aid landscape.

Malawi’s situation highlights wider issues within the global aid system, exposing systemic flaws in how aid is distributed and implemented.

There is a strong need for more effective strategies that prioritize development through local engagement. Additionally, creating mechanisms to leverage funds will lead to more impactful and lasting assistance for countries in need.